Pennine Lines w/c 23 September 2024

|| Wet but improving || Keep the faith ||

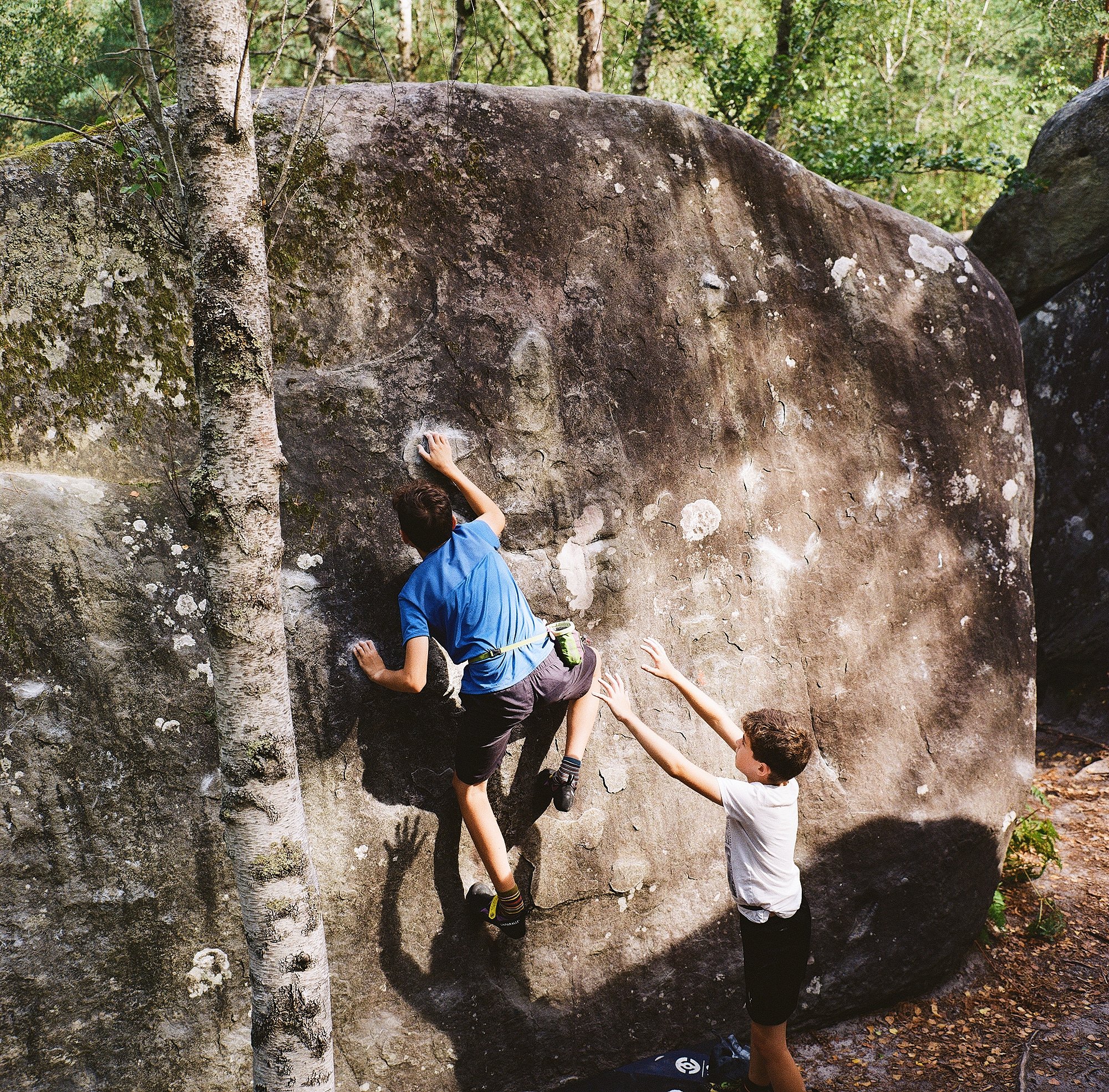

Haute Pierre on film || Fontainebleau

|| Focus On... ||

Font vs UK

OK it’s rained solidly for the last few days, so I can’t force myself to think about gritstone, or the burning-a-hole-in-my-project-list unfinished limestone problems which may just have gotten wet for the next eight months. Instead, having recently run a workshop on film photography I found myself glancing back on some film images from Fontainebleau from this summer and last, thinking about Font and the differences compared to how bouldering evolved in the UK.

One thing I keep coming back to time and time again is how bouldering in Font at the easier end of the spectrum - the kids' circuits, the yellow and orange and blue circuits - is just infinitely better than the bouldering of an equivalent standard at the majority of UK venues. Not strictly in terms of quality, although that is a factor, but more in terms of weight of numbers; there’s just much more to go at in Font by a factor of about a thousand. Good quality easier stuff in Font is just everywhere, whereas in the UK it can be very slim pickings, not least because most of our best lower-end climbing is on trad routes, not on boulders.

Geology drives this in an immediate sense, because the rock in Font does, for all its reputation for featureless slopers, boast very heavily featured forms, which somehow lend themselves to being the right size and with enough holds for interesting easier climbing. Perhaps more so than UK rock somehow. When you look at the kids' circuits in Font in particular you come to realise there could be at least ten times the number of existing ones (and there are a lot), the only limit being that someone needs to go out and clean up a load of smaller boulders and paint 'em up - but they are there, in huge numbers.

Franchard Sablons summer circuits || Fontainebleau

But there is something of a cultural aspect to the difference between the development of bouldering in Font versus the UK too. Being geographically detached from the hotbeds of French climbing in the Alps and the south, Font climbing history seems to be at peace with the fact that it’s ‘only’ bouldering (bar some of those really high toprope lines like the Mauve death circuit at Dame Jouanne). That’s just what it is here, and other than driving 400 miles south that’s what you’re stuck with, like it or not. The boulders are not competing for your affection with huge crags towering above them. So whereas the focus nationally may have been on routes and alpine climbing, Font climbers addressed this need by creating circuits of dozens and dozens of problems interlinked, to approximate an alpine route - and by necessity this means finding lots and lots of easier problems, because move-for-move alpine routes at the PD, AD and D standard aren’t very hard by rock climbing standards. Hence the magnificent yellow, orange and blue circuits. You will note that if you follow a Font circuit properly from the very beginning, the ‘Depart’ is still marked with an alpine grade.

The UK development of bouldering was a bit different though. Again driven by geology, most of our climbable rock, the best stuff, was always on routes. And no matter whether it was mountain or crag based, most of the big obvious appealing crags didn’t afford us the courtesy of stopping after four meters of height. Hence bouldering was, for a long time, second fiddle to routes. Only the most prominent and attractive bouldering features would be recorded and named, and they’ve have to be situated at a trad crag in the first place - hence the likes of Joe’s Arete, Not To Be Taken Away and Crescent Arete. The sort of thing the trad climber might want to do for training at the end of a long afternoon to sharpen their technique. And since bouldering was for training, bouldering was hence quite hard - in fact it had to offer moves as hard or harder than the hard routes to be worth doing. This explains why you can, to this day, turn up at a lot of grit crags and find apparently unclimbed and unrecorded easier problems or gaps where easy problems could exist, because it wasn’t until guides started to be produced in the 1990s that they would be recorded at all, and most weren’t given names until the routes-as-database-records era was reached much later. Meanwhile in Font all those easier problems would be recorded by way of paint arrows and inclusion in circuits.

Rocher de la Reine || Fontainebleau

The culture of considering bouldering as only being worthy as training for routes persisted well into this century, and it carried over into indoor climbing too. In fact it wasn’t until the mid to late 2000s that you could turn up at an indoor wall as a beginner and do any beginner-level or easy bouldering at all. It just wasn’t catered for, so as a beginner you would scarcely get much bouldering done for your £4.50 entrance fee (sigh). The easier climbing was on ropes, and that was that. In retrospect this was odd, but it just reflected the prevailing trends at the time. Bouldering was supposed to be hard, to be training, you were supposed to serve an apprenticeship of “proper” climbing on ropes. You weren’t really supposed to do bouldering to the exclusion of all else.

It’s not really until the post-Climbing-Works modern era of purpose built bouldering walls that easier problems or circuits emerged. In many ways this has been at the heart of the success of more recent modern walls in accommodating the beginner, the lower grade climber, kids and anyone who needs more accessible bouldering. Modern walls have brushed the intertwined historical and geological context aside and dispensed with the cultural baggage, and made a complicated situation easy to understand for the newcomer by just catering much better for easier bouldering, no questions asked. You don’t have to turn up to the wall and understand the history of why there’s no easy stuff like you did in the 1990s, instead you can turn up and crack on, follow the colours and enjoy the challenge; job’s a good ‘un.

If there’s a downside to this it’s that some of that lost historical and cultural baggage actually has some items of value within. Namely all the stuff about not climbing wet gritstone and sandstone, the contentious nature of chalk use, overcrowding, and how you should act in the countryside, not playing music at the crag, and all the trials and tribulations of obtaining and retaining access to crags. That will be an ongoing issue that we as climbers needs to grapple with, just as in Fontainebleau they have been recently battling the issue of irresponsible van use and wet rock damage. Hopefully the way forward on these issues will be supported by the climbing walls and not just be left to local activists to pick up the pieces (literally, in the case of broken holds). On that note if you or any of your mates didn’t catch the Stay Classy project that I worked on last year in conjunction with The Depot, check it out here.

Somewhere in the Forest.... || Fontainebleau

|| Recently Through The Lens ||

A perennial favourite for the taller gent; Desperation at Stanage. A great route up a plumb vertical wall at an amenable grade - lovely stuff.

|| Fresh Prints ||

A couple of favourites from Stanage, the home of so many classic mid-grade trad routes, in the Print Shop.